[CVE-2026-0714] TPM-sniffing LUKS Keys on an Embedded Device

Executive Summary

Trusted Platform Modules (TPM 2.0) are widely used to protect storage encryption keys and provide hardware backed attestation. While TPM bus sniffing attacks against Windows systems with BitLocker are well documented, less research has focused on non-BitLocker targets such as embedded Linux devices using LUKS.

In this work, we demonstrate that the Moxa UC-1222A Secure Edition releases its full LUKS device decryption key in plaintext during boot via a TPM2_NV_Read operation bound to PCR policy. Although the TPM enforces authorization correctly, the returned key material is transmitted unencrypted over the SPI interface. By passively monitoring the SPI bus between the SoC and the discrete TPM 2.0 device, the LUKS decryption key can be recovered and used to decrypt the encrypted storage.

The issue has been acknowledged by Moxa and assigned CVE-2026-0714.

Introduction

In October 2025, we performed a security assessment of the ARM-based Moxa UC-1222A Secure Edition industrial computer. The UC-1200A series is described by the vendor as follows:

The UC-1200A computing platform is designed for embedded data-acquisition applications. [...] With flexible interfacing options, this tiny embedded computer is a reliable and secure gateway for data acquisition and processing at field sites as well as a useful communications platform for many other large-scale deployments.

The device is marketed as a hardened platform and supports full disk encryption backed by a discrete TPM 2.0 chip.

Threat model

We assumed that an adversary had physical access to the device, under conditions where they are able to use specialized hardware tools to probe and tamper with the device.

Given the use of a discrete TPM connected over SPI, we evaluated whether passive bus monitoring during the boot process could expose sensitive key material.

Previous work

Passive bus sniffing attacks against TPM 2.0 have been demonstrated in multiple contexts, particularly against BitLocker-enabled Windows systems1 2 3. These attacks typically target the BitLocker Volume Master Key, which is released by the TPM during the boot process and used to decrypt the protected volume.

There have also been successful TPM sniffing attacks against non-BitLocker targets. Jos Wetzels demonstrated that Linux devices using Clevis with a discrete TPM to unlock LUKS-encrypted disks are vulnerable to SPI sniffing, allowing an attacker with physical access to extract a JWK from TPM SPI traffic and reconstruct the device decryption secret.4

However, little public research has examined whether the same attack class applies to embedded and industrial Linux systems. Such devices may rely on vendor specific initramfs hooks and custom provisioning logic rather than using solutions like Clevis. It is not clear how or if key material is exposed over the TPM bus for such devices.

Furthermore, for embedded devices deployed in unmonitored or in remote environments, prolonged physical access by an adversary may be more likely than for example a client laptop. With this research, we hope to demonstrate what a successful TPM sniffing attack on an embedded device may look like.

Background

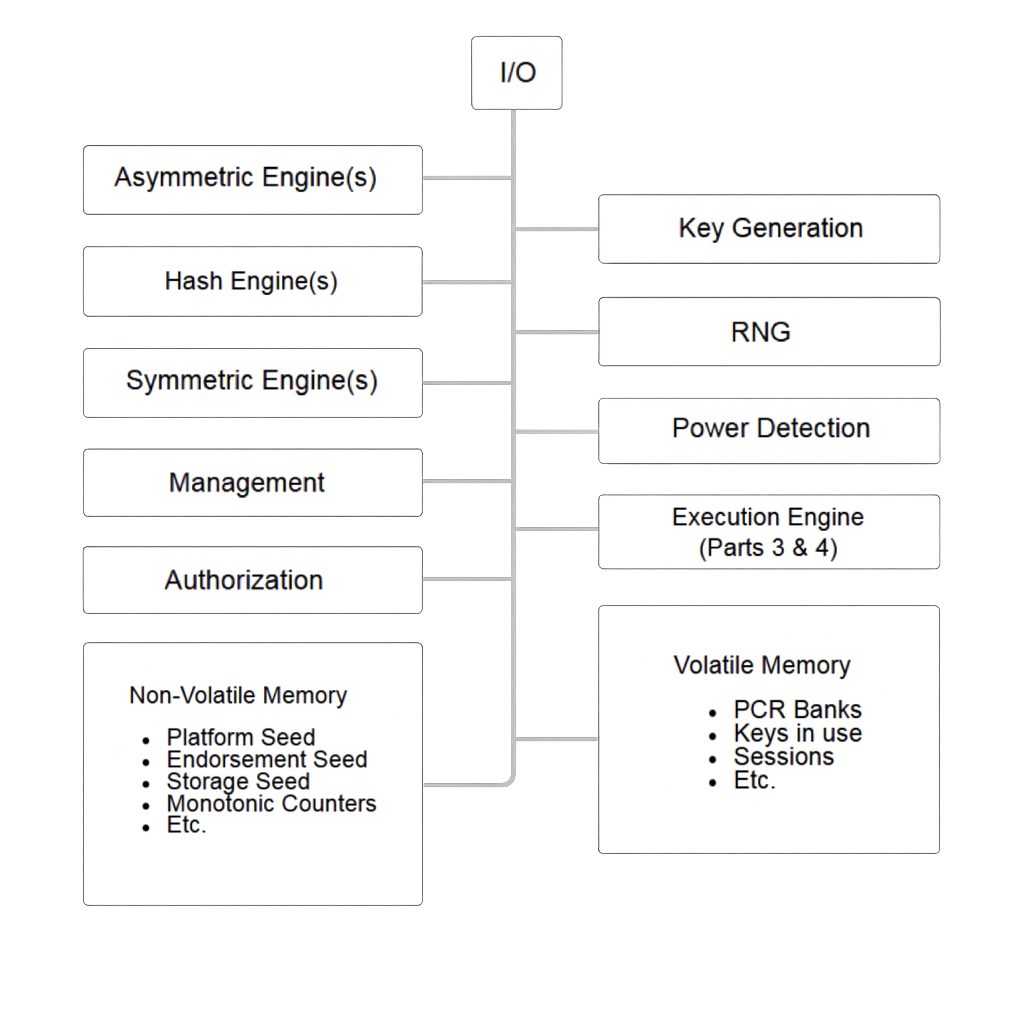

TPM 2.0 architecture overview

The Moxa UC-1222A Secure Edition employs a discrete TPM 2.0 device as both a root of trust for attestation and as a protection mechanism for storage decryption keys. The TPM maintains persistent root secrets within its internal non-volatile memory, including seeds that form the basis of its key hierarchies, as described in the TCG TPM 2.0 Library Specification (Part 1)5.

Rather than storing the device decryption key directly in system storage, the key is generated during provisioning of the device and then protected by the TPM under authorization policies. The TPM's internal root secrets never leave the chip. Instead, they are used to enforce policy and protect TPM objects such as the device decryption key.

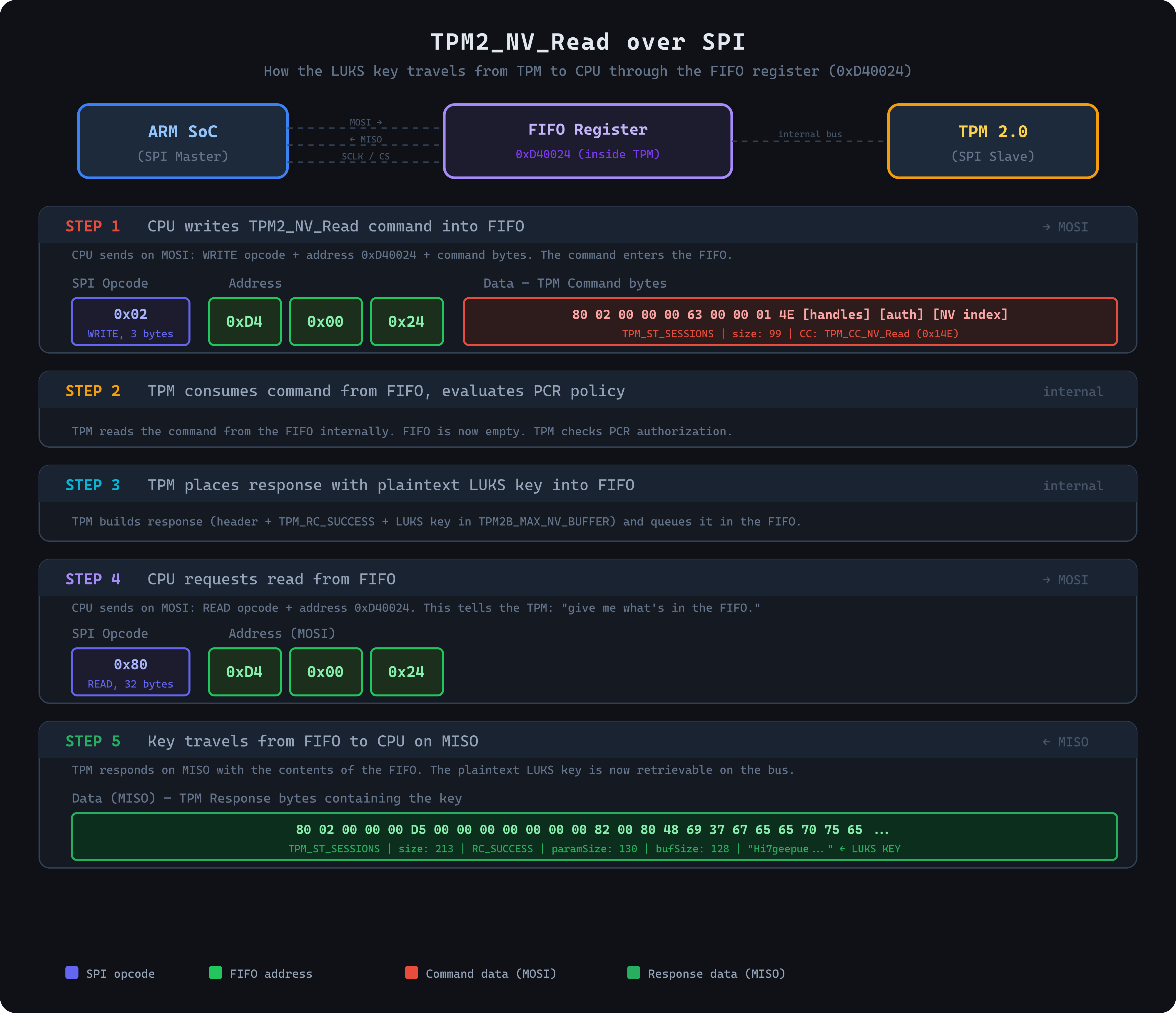

During boot on the Moxa UC-1222, the host SoC issues TPM commands to read the contents of this protected NV index as part of the TPM's structured command–response protocol. If the authorization policy is satisfied, the TPM returns the key material, which we will refer to as the LUKS disk key, to unlock the encrypted partition.

More generally, passive TPM bus sniffing attacks exploit this pattern:

- An application-level secret (LUKS device key) is provisioned into the TPM and later retrieved by the host during boot.

- Although the TPM enforces authorization policy correctly, the retrieved data is transmitted in plaintext over the SPI interface, allowing a physically capable adversary to recover it by monitoring the bus.

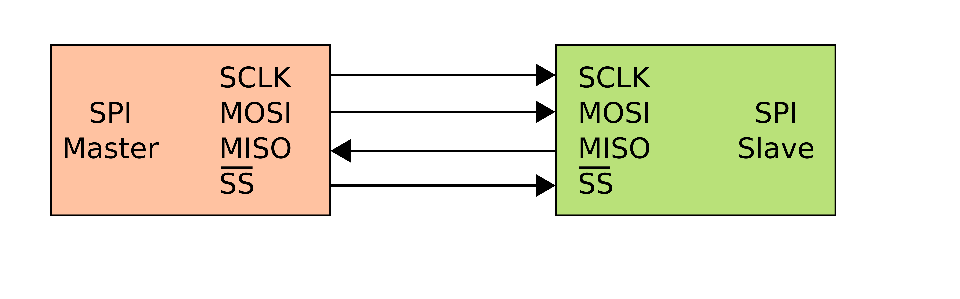

SPI Interface

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) is a synchronous serial communication bus used for communication between the discrete TPM and the ARM SoC. The SoC operates as the SPI master, while the TPM functions as an SPI slave.

SPI communication is based on four primary signals:

- SCLK (Serial Clock) – Generated by the master to synchronize data transfers.

- MOSI (Master Out, Slave In) – Carries data from the master (CPU) to the slave (TPM).

- MISO (Master In, Slave Out) – Carries data from the slave (TPM) to the master (CPU).

- SS / CS (Slave Select / Chip Select) – Asserted by the master to select a specific slave device and initiate a transaction.

Firmware Analysis

The Moxa firmware image is publicly available from the vendor at the following link.

We extracted the first partition, which contains an initrd image, and examined the startup scripts located under moxa-initrd-init/hooks.d/ to identify TPM-related operations executed during early boot.

We identified the generate-keys script as particularly relevant, as it contains logic for handling cryptographic keys. The relevant portion of the script invokes the tpm2_nvread utility to access a defined NV index associated with the LUKS device key:

device_luks_key=$(tpm2_nvread -T device:"${TPM2_DEV}" -P "pcr:${PCRS_SELECTION}" "${DEVICE_LUKS_KEY_INDEX}")This command issues a TPM2_NV_Read operation against the NV index identified by DEVICE_LUKS_KEY_INDEX, with authorization bound to the specified PCR selection. Because this operation results in a structured command–response exchange over the SPI interface, the response can be identified in captured SPI traffic.

Hardware Setup

Target TPM

The Moxa UC-1222A uses an Infineon SLB9670 TPM 2.0 chip for key storage. The pinout can be seen below from the official datasheet6.

As described in the SPI section, the following pins were needed to sniff SPI bus traffic.

| Pin | Signal | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CS# | Chip Select (active low) |

| 2 | MISO | Master In, Slave Out |

| 3 | MOSI | Master Out, Slave In |

| 4 | SCLK | Serial Clock |

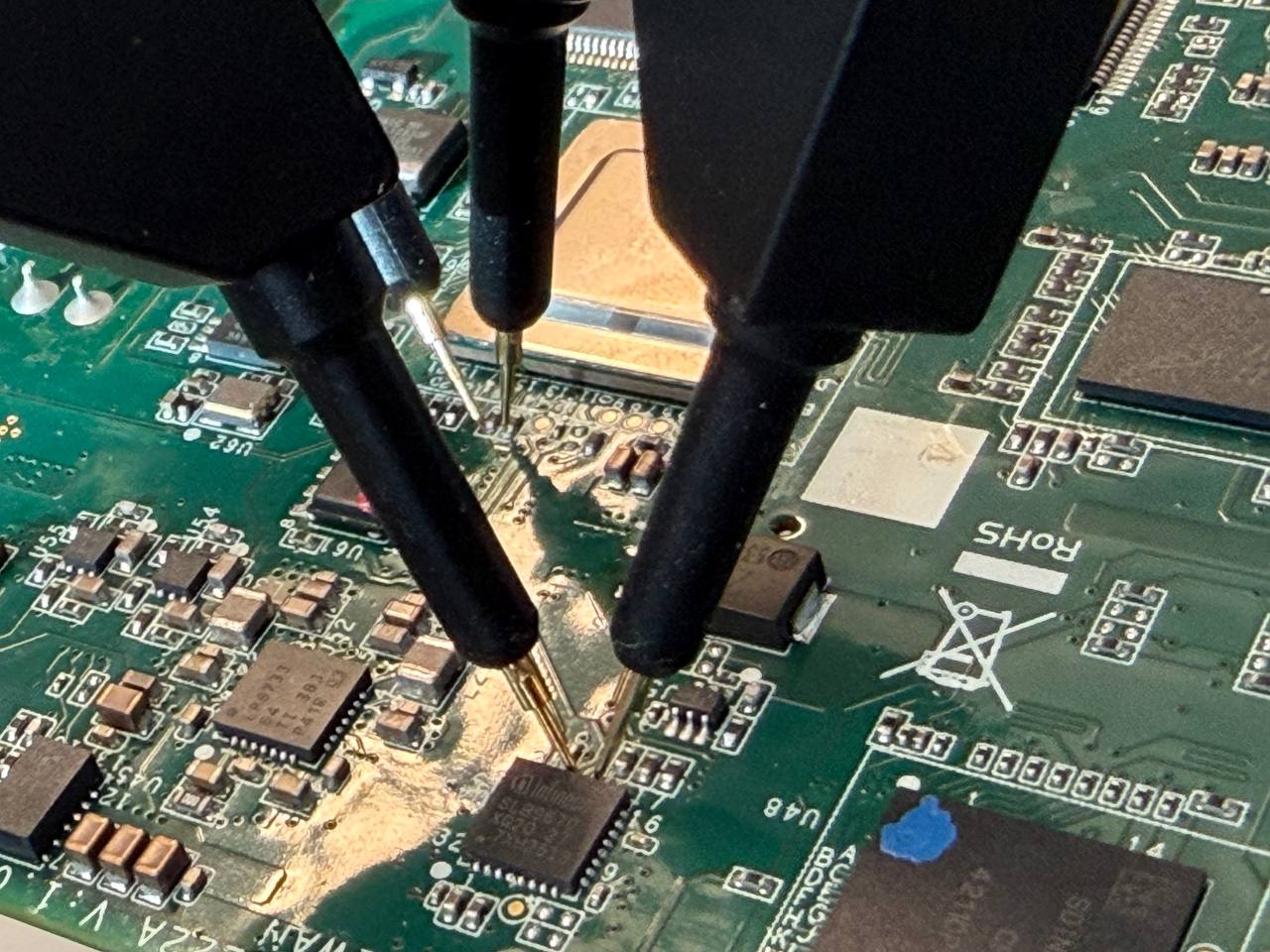

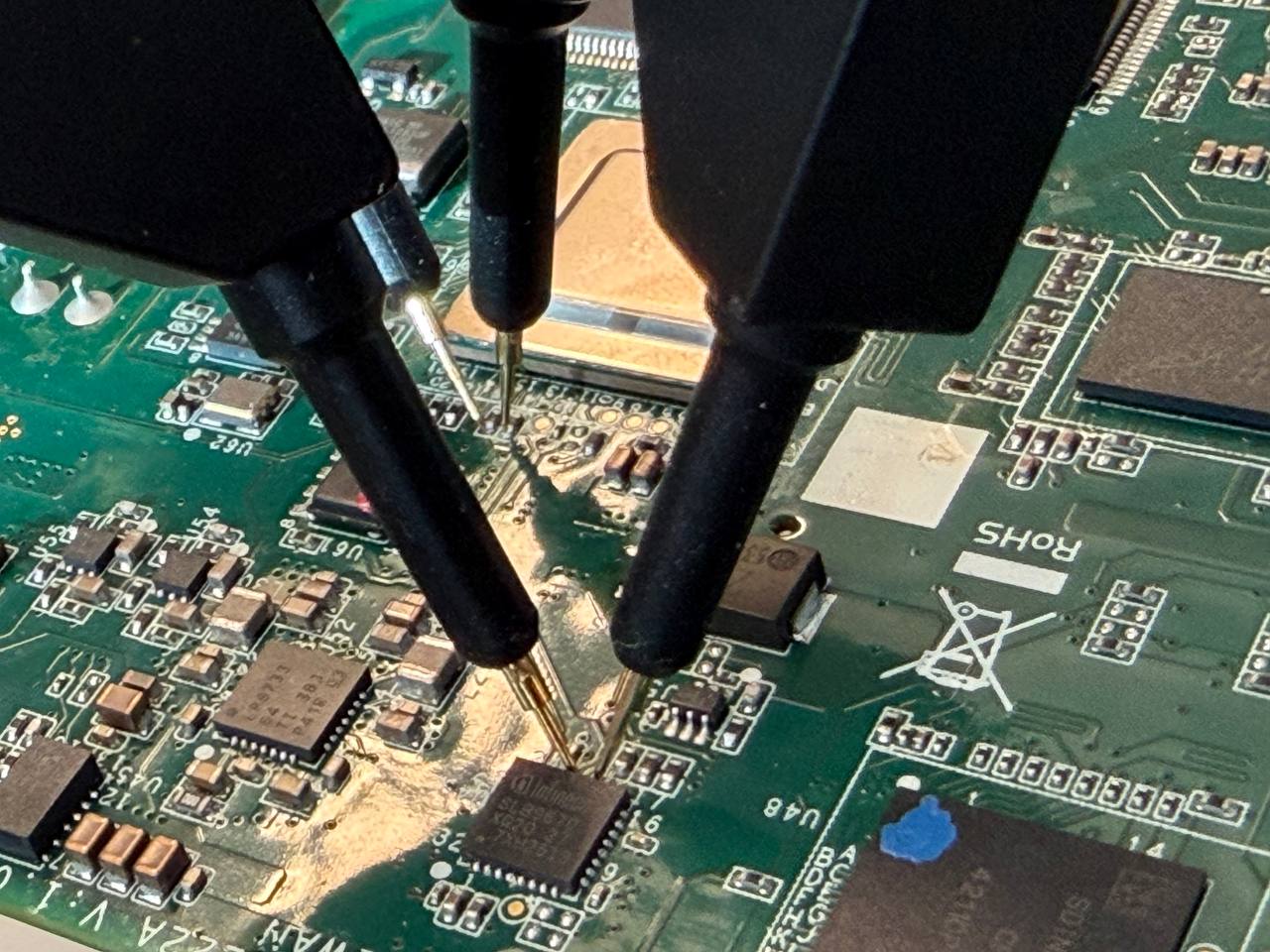

Logic Analyzer Connection

To conduct the passive bus sniffing attack, a Logic 8 Saleae 8-channel logic analyzer was used.

In the table below, the setup for the Saleae can be seen.

| Saleae Channel | TPM Pin | Signal |

|---|---|---|

| CH0 (Green) | 1 | CS# |

| CH1 (Blue) | 4 | SCLK |

| CH2 (Purple) | 2 | MISO |

| CH3 (Yellow) | 3 | MOSI |

Sniffing the SPI Bus

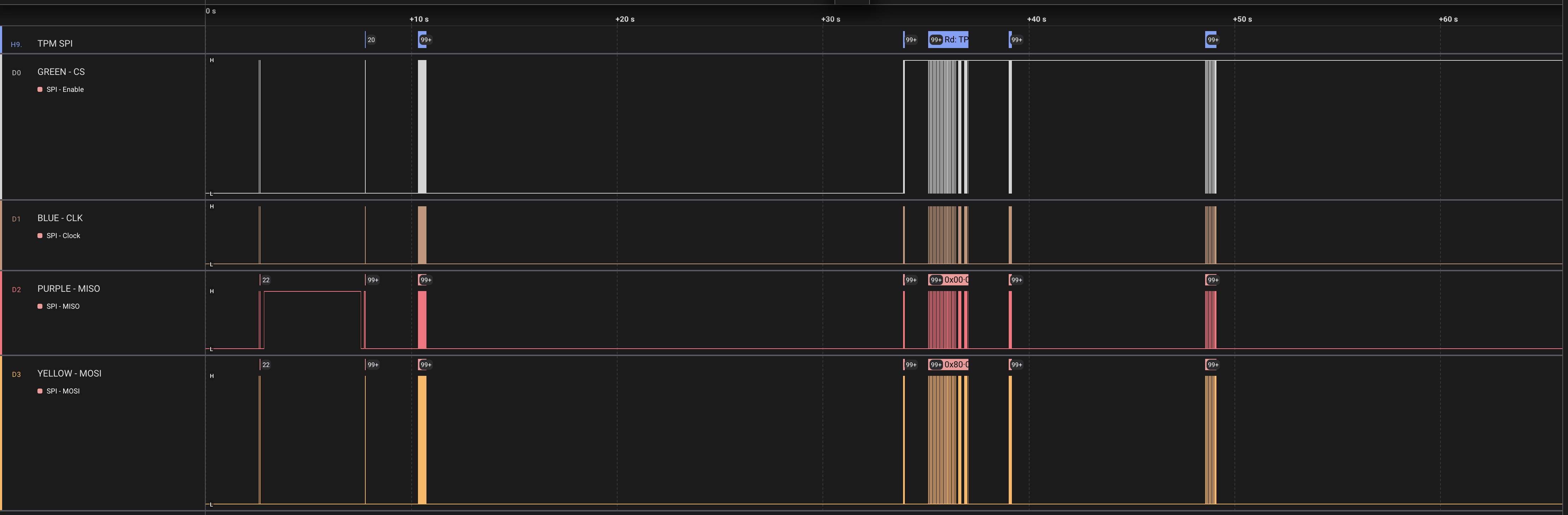

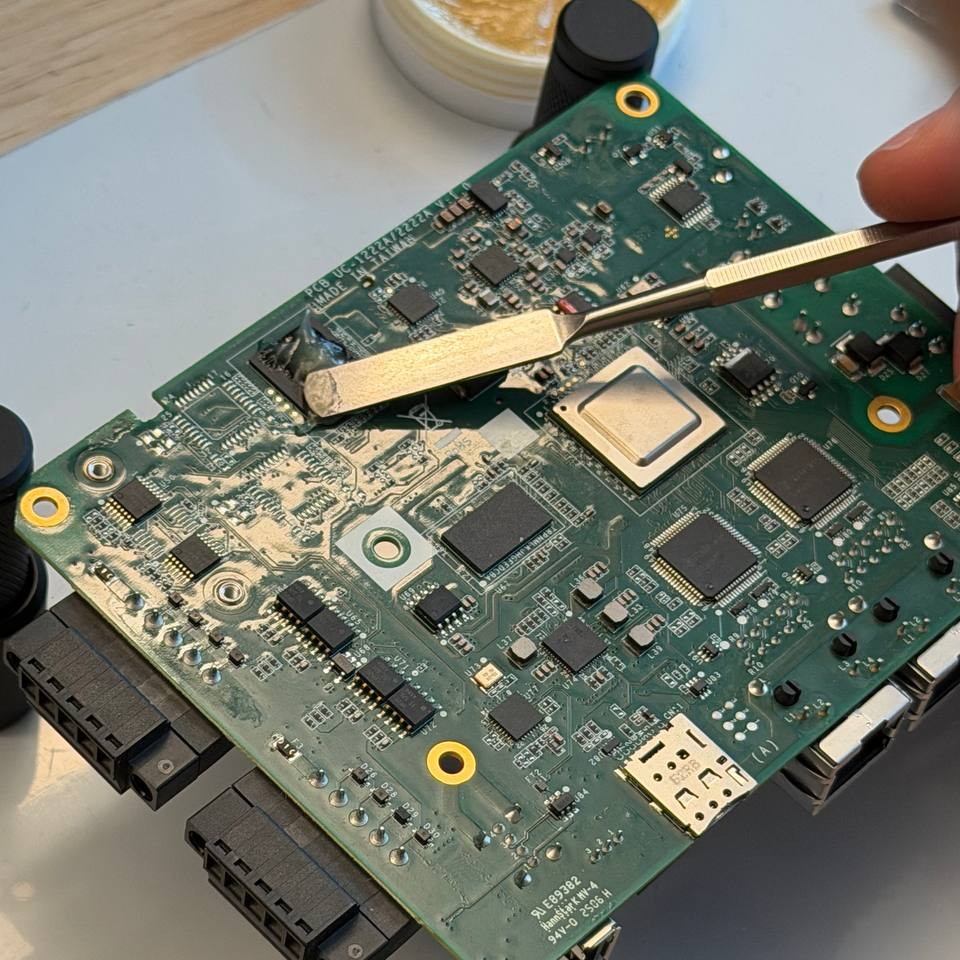

In order to sniff the bus traffic, the following Logic analyzer setup was used for the probes.

The CS and SCLK probes were attached to the Infineon TPM's SPI interface, while the MISO and MOSI probes were attached to measurement points along the same signal nets, instead of directly on the TPM's MISO and MOSI pins for easier attachment. The ground pin cannot be seen in the above figure, since it was attached to a ground point on the opposite side of the PCB.

Logic 2 was configured to use a reading speed of 250 MS/s at 3.3+ Volts for the full bootup time, which was around ~50 seconds.

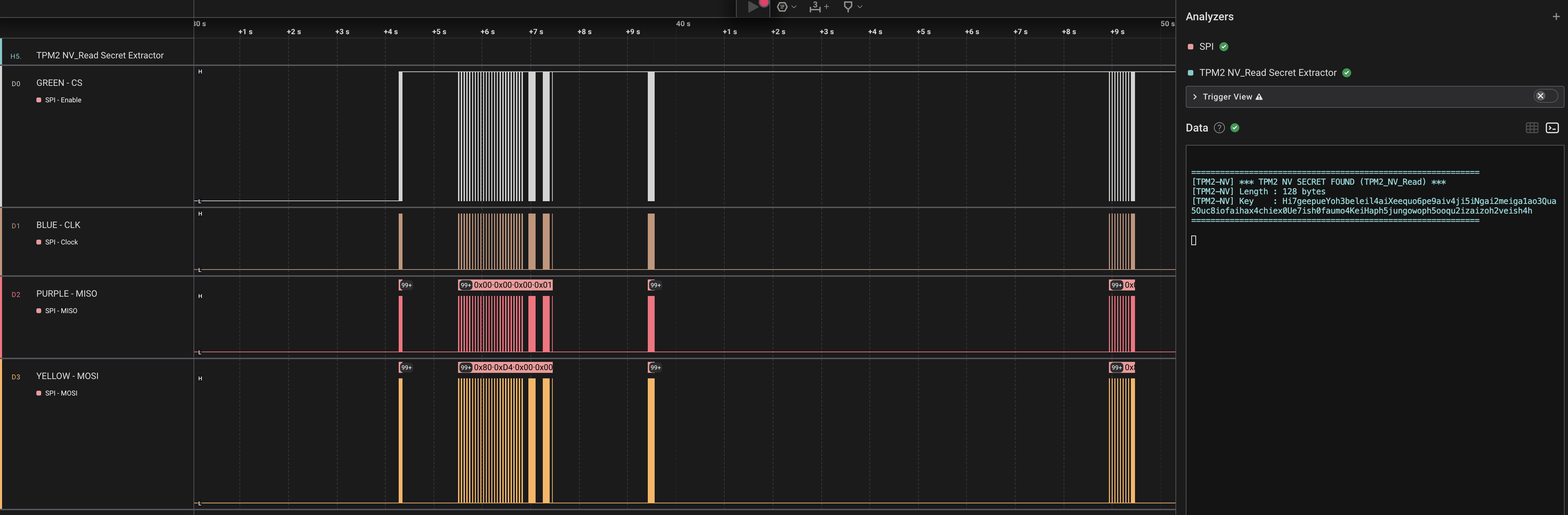

With the probes attached and Logic Pro configured, the Moxa UC 1222A was booted and the following traffic was recorded

Logic 2 allows captured traffic to be exported as a CSV. This data can be analyzed to understand the exchange between the TPM and the SoC. Two custom scripts were made to parse the data and extract the TPM 2.0 commands.

Table 14 in TCG's TPM2 Part 2: Structures document reveals the command code that we are interested in7. The TPM_CC_NV_Read command corresponds to the 0x0000014E command code. The tpm2_spi_decoder script can parse the data and provide offsets and command codes for the MOSI stream. If we grep for 0x0000014E we can see the following:

python3 tpm2_spi_decoder.py digital_TPM_EXPORT_raw.csv | grep "0x0000014E"

Which tells us the offset where the TPM_CC_NV_Read command is sent. In order to see the response, we need to analyze the MISO stream around that offset. The tpm_spi_carve.py script provides that feature with the following flags. Alternatively, we can use the tpmstream program provided by the tpm2-software community8.

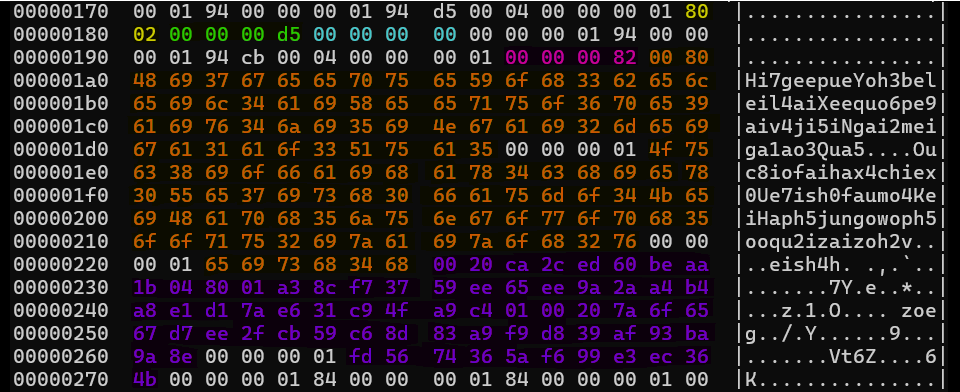

python3 tpm_spi_carve.py digital_TPM_EXPORT_raw.csv --carve-after-offset 23870 --carve-dir miso --carve-hex key.txt --carve-bin key.binThis results in a binary which can be viewed with the hexdump tool.

hexdump -C key.binThe captured SPI stream contains a complete TPM2_NV_Read response. The response bytes are color-coded in the hex view.

The tag value TPM_ST_SESSIONS (0x8002) indicates that the response includes both a parameterSize field and a session area containing a TPMS_AUTH_RESPONSE structure. The parameters section contains the TPM2B_MAX_NV_BUFFER returned by the command, while the trailing session area carries the authorization response data.

Using the structure definitions from TPM 2.0 Part 2 and the command definition from Part 3, the SPI response can be parsed as shown below. Each color in the hex view corresponds sequentially to a row in the table, from top to bottom.

| Name | Type | Contents | Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| tag | TPM_ST | 80 02 | TPM_ST_SESSIONS |

| responseSize | UINT32 | 00 00 00 d5 | Response Size (213 bytes) |

| responseCode | TPM_RC | 00 00 00 00 | TPM_RC_SUCCESS |

| parameterSize | UINT32 | 00 00 00 82 | Parameter Size (128 + 2 bytes) |

| data | TPM2B_MAX_NV_BUFFER | 00 80 48 69 ... | Buffer size + NV Data |

| authResponse | Several | 00 20 ca 2c ... | TPMS_AUTH_RESPONSE |

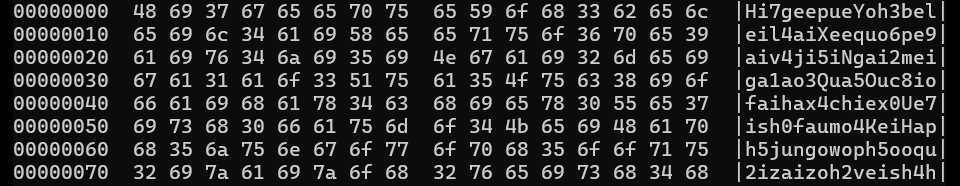

The orange-colored part of the hex view shows the response data, containing the LUKS device key in plaintext. After being carved out it can be viewed in its entirety.

python3 tpm_spi_carve.py digital_TPM_EXPORT_raw.csv --carve-after-offset 23870 --carve-

after-length 417 --carve-count 136 --carve-dir miso --carve-hex key.txt --carve-bin key.bin ;

xxd -p key.bin | tr -d '\n' | sed 's/00000001//g' | xxd -r -p > out.binhexdump -C out.bin

The secret below can be used to decrypt the LUKS encrypted partitions on the device and access the storage.

Hi7geepueYoh3beleil4aiXeequo6pe9aiv4ji5iNgai2meiga1ao3Qua5Ouc8iofaihax4chiex0Ue7ish0faumo4KeiHaph5jungowoph5ooqu2izaizoh2veish4hData flow diagram

The full command-response flow over SPI is summarized in the diagram below.

Automated Key Extraction

We have made a Saleae plugin for automatically extracting the NV_Read secrets on our GitHub.

Key Validation

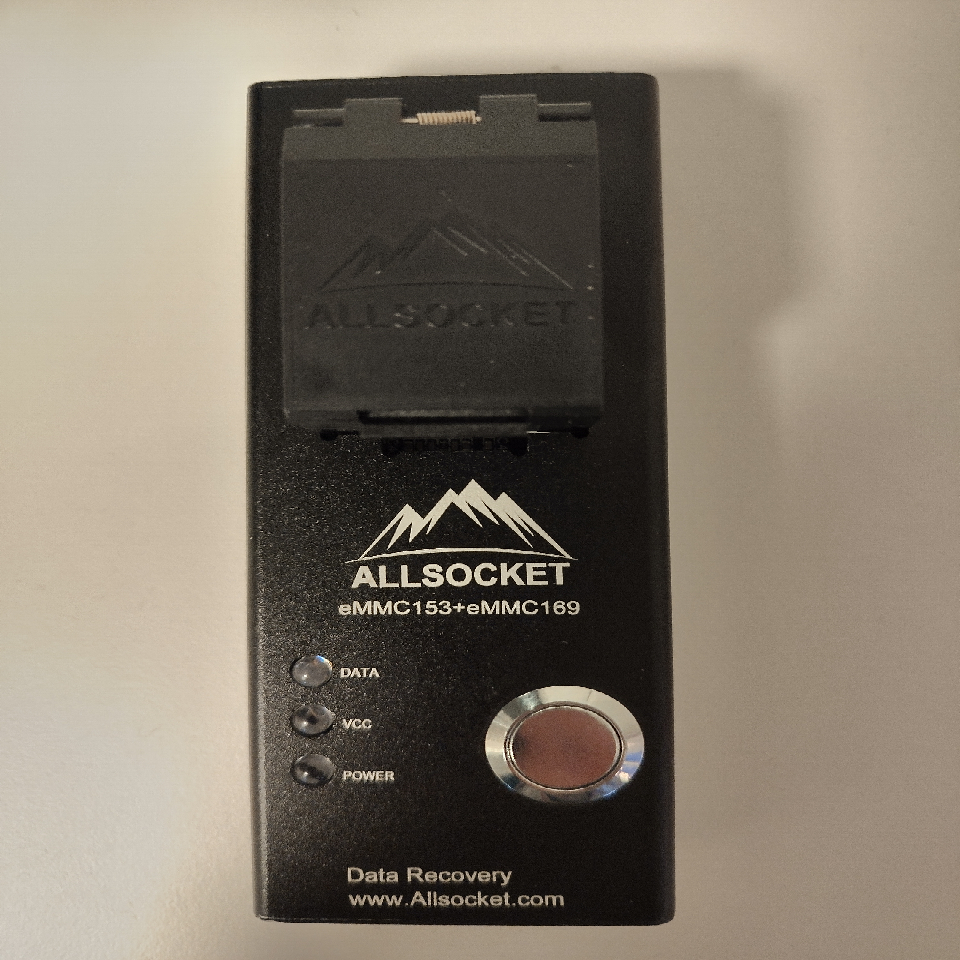

In order to confirm the validity of the key, the eMMC flash chip was de-soldered using hot-air soldering and the chip was mounted and read using an Allsocket eMMC153 reader. The process is shown below.

Step 1: Apply soldering flux

Soldering flux is applied to the eMMC flash chip.

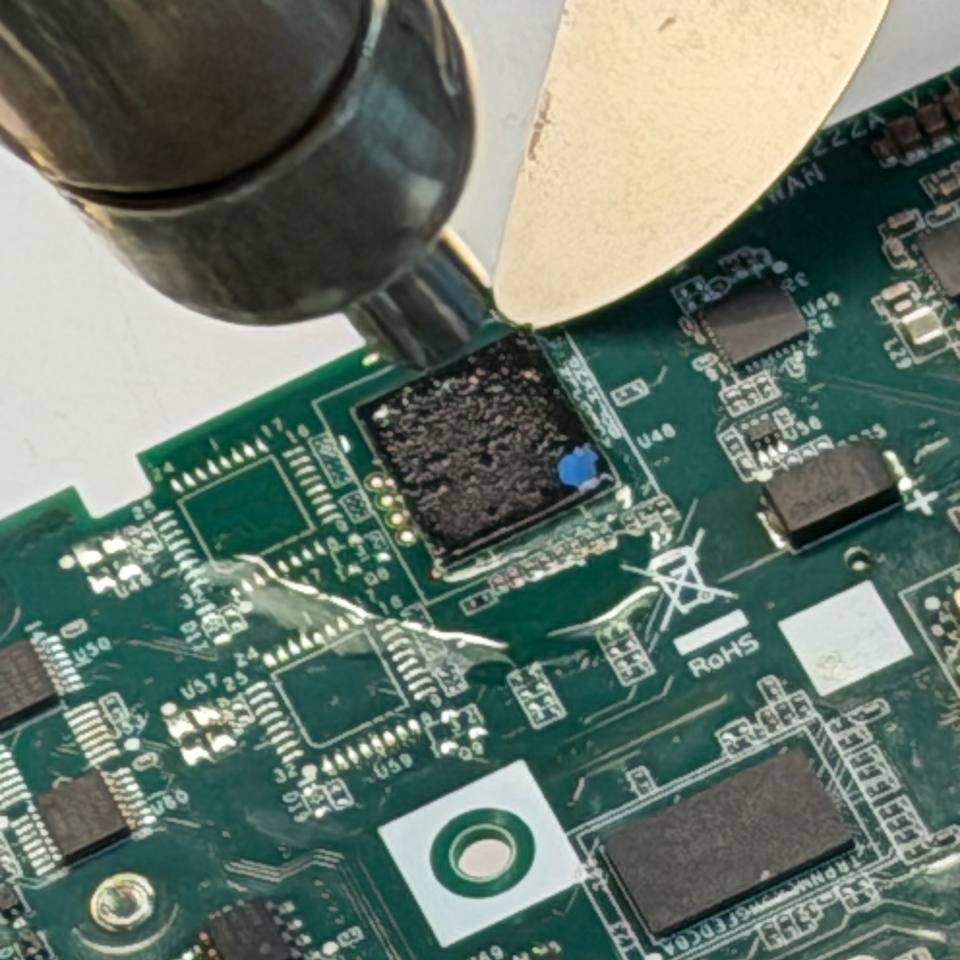

Step 2: De-solder the chip

The eMMC chip is removed using hot-desoldering.

Step 3: Remove paste

Residue was removed from the eMMC using a soft (nylon) toothbrush and 99% isopropyl alcohol, then allowed to dry.

Step 4: Read the eMMC chip data

The eMMC data was read using an Allsocket eMMC153 reader and made into an image with

sudo dd if=/dev/disk9s3 of=emmc_moxa_dump_full5.img bs=4m status=progress

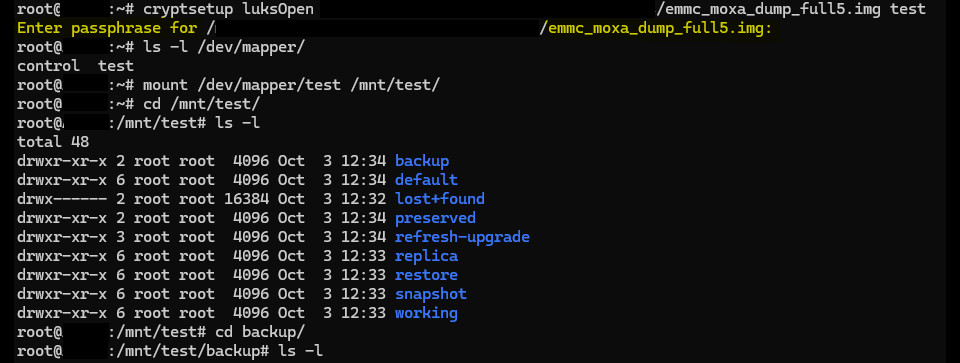

Step 5: Mounting the image and successfully testing the passphrase

The encrypted image was then mounted, at which point the passphrase, or LUKS device key, was entered. The screenshot below shows the image being successfully mounted after entering the passphrase. This validates that the sniffed passphrase is correct.

Discussion

If your device uses a discrete TPM and your threat model includes physical access, you must account for TPM bus sniffing attacks. This work demonstrates that this device isn't restricted to a client PC or laptop, but could also be an embedded system or industrial computer.

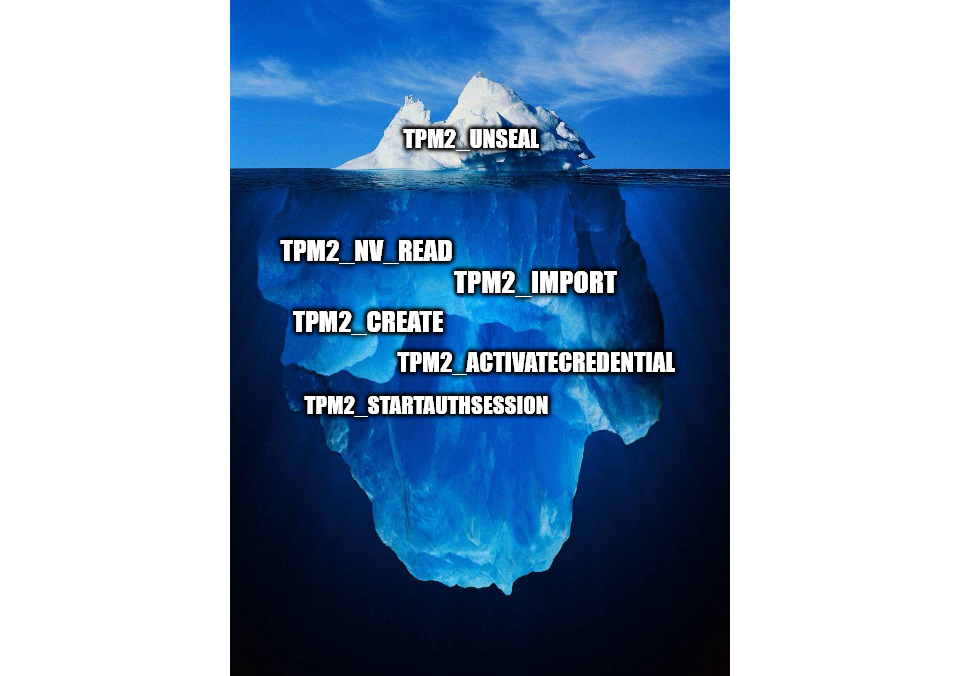

The modification needed to perform a TPM bus sniffing attack on our Moxa compared to on a Bitlocker-enabled system was relatively small. BitLocker typically relies on TPM2_Unseal to release a sealed object, whereas the Moxa device retrieves the key from a policy-protected NV index using TPM2_NV_Read. In previous work, TPM2_Unseal has by far been the most commonly observed command in these types of attacks, to the point of almost becoming synonymous with the TPM releasing its disk decryption secret. To our knowledge, this is the first publicly documented TPM sniffing attack where TPM2_NV_Read has been the mechanism releasing the key. Although the TCG has previously described this method of releasing key material in their CPU–TPM Bus Protection Guidance document9, we speculate that similar implementations may exist in the wild.

Mitigations

Trusted Computing Group (TCG) provides guidance for mitigating passive bus monitoring attacks in TCG CPU–TPM Bus Protection Guidance9. The specification supports parameter encryption through authorization sessions, allowing sensitive command and response parameters to be protected in transit between the host and the TPM.

Encrypted sessions are established using combinations of tpmKey and bind parameters, resulting in unbound, bound, salted, or salted and bound session types. Bound sessions derive their security from the entropy of an existing object's authValue, while salted sessions use asymmetric cryptography to establish a shared session key without requiring a pre-existing secret.

For bootups where the user does not enter a PIN, and no high-entropy authValue is available, bound sessions do not provide meaningful protection. Salted sessions, however, can protect command and response parameters even without user input. A disadvantage to this session choice is a slower setup due to asymmetric key exchange.

References

- Denis Andzakovic – Extracting BitLocker keys from a TPM

- Henri Nurmi – Sniff, there leaks my BitLocker key

- Guillaume Quéré – Bypassing Bitlocker using a cheap logic analyzer on a Lenovo laptop

- Jos Wetzels – TPM Sniffing Attacks Against Non-Bitlocker Targets

- Trusted Computing Group – Trusted Platform Module 2.0 Library Part 1: Architecture

- OPTIGA – TPM SLB 9670 Datasheet

- Trusted Computing Group – Trusted Platform Module 2.0 Library Part 2: Structures

- tpmstream-web

- Trusted Computing Group – CPU–TPM Bus Protection Guidance

Kontakta oss

Vill du också ligga steget före hoten?

Vi slår ut svagheterna innan de hinner bli risker, granskar din säkerhet med kirurgisk precision och hjälper dig bygga upp ett försvar som inte viker sig för något.